LE SITE DU JBEL IRHOUD

• LE SITE DU JBEL IRHOUD Ce site est désormais connu mondialement en raison de l’importance des découvertes archéologiques qui y ont été faites. Celles-ci débutèrent en 1961 lorsqu’un ouvrier de la société minière exploitant la barytine à JbelIrhoud découvrit un crâne humain. Cette découverte, connue depuis sous le nom de l’homme d’Irhoud, fut suivie de fouilles archéologiques dirigées par Emile Ennouchi, de la faculté des Sciences de Bordeaux et qui donnèrent lieu à la découverte de deux nouveaux crânes attribués à l’époque, au néanderthalien, ainsi que des débris osseux et quelques outils en pierre du Moustérien.

Une première estimation fait remonter l’âge des deux crânes à 50.000 ans, mais d’autres analyses entreprises en 1980 (Hublin, Institut d’Archéologie du Musée de l’Homme rattaché au Collège de France) sur la mâchoire inférieure de l’homme d’Irhoud (un enfant, en réalité) avancent l’âge de 80 à 125.000 ans. L’hypothèse plausible serait celle d’un âge de 100.000 ans, ce qui fait de l’homme d’Irhoud, sinon le plus ancien, du moins l’un des plus anciens homosapiens au monde.

(ETUDE SUR LES POLES D’ECONOMIE DU PATRIMOINE DIAGNOSTIC STRATEGIQUE DES RESSOURCES PATRIMONIALES DE LA REGION DE DOUKKALA-ABDA Rapport Provisoire PHASE 1 Octobre 2007 Pierre-Antoine Landel, Nicolas Senil, Pascal Mao To cite this version: Pierre-Antoine Landel, Nicolas Senil, Pascal Mao. ETUDE SUR LES POLES D’ECONOMIE DU PATRIMOINE DIAGNOSTIC STRATEGIQUE DES RESSOURCES PATRIMONIALES DE LA REGION DE DOUKKALA-ABDA Rapport Provisoire PHASE 1 Octobre 2007. Rapport provisoire 2007.)

Jebel Irhoud or AdrarIghud(Moroccan Arabic: ??? ?????, translit. žb?li?ud pronounced ; Berber: ??????????adrar n i?ud) is an archaeological site located just north of the locality known as TletIghoud, about 50 km (30 mi) south-east of the city of Safi in Morocco. It is noted for the Hominin fossils that have been found there since the site's discovery in 1960. Originally thought to be Neanderthals, the specimens have since been assigned to Homo sapiens and have been dated to over 300,000 years old. If correct, this would make them by far the oldest known fossil remains of Homo sapiens.[1] [2] [3]

Finds

The site is the remnants of a solutional cave filled with 8 meters (26 ft) of deposits from the Pleistocene era, located on the eastern side of a karstic outcrop of limestone[4] at an elevation of 562 meters (1,844 ft).[5] It was discovered in 1960 when the area was being mined for the mineral baryte.[4] A miner discovered a skull in the wall of the cave, extracted it and gave it to an engineer, who kept it as a souvenir for a time. It was eventually handed over to the University of Rabat, who organized a joint French-Moroccan expedition to the site in 1961, headed by the French researcher ÉmileEnnouchi.[6]

Ennouchi's team identified the remains of around 30 species of mammals, some of which are associated with the Middle Pleistocene, but the stratigraphic provenance is unknown. Another excavation was carried out by Jacques Tixier and Roger de Bayle des Hermens in 1967 and 1969 in which 22 layers were identified in the cave. The lower 13 layers were found to contain signs of human habitation including an industry classified as Levallois Mousterian.[4]

The site is particularly noted for the hominin fossils found there. Ennouchi discovered a skull which he termed Irhoud 1 and is now on display in the Rabat Archaeological Museum. He discovered part of another skull, designated Irhoud 2, the following year and subsequently uncovered the lower mandible of a child, designated Irhoud 3. Tixier's excavation found 1,267 recorded objects including skulls, a humerus designated Irhoud 4 and a hip bone recorded as Irhoud 5. Further excavations were carried out by American researchers in the 1990s and by a team led by Jean-Jacques Hublin from 2004.[5] [7] Animal remains found at the site have enabled the ancient ecology of the area to be reconstructed. It was quite different to the present and probably represented a dry, open and perhaps steppe-like environment roamed by equids, bovids, gazelles, rhinoceros and various predators.[8]

Dating

The finds were initially interpreted as Neanderthal, as the stone tools found with them were believed to be associated exclusively with Neanderthals.[9] [10] They also had archaic features believed to be representative of the Neanderthals, rather than Homo sapiens. They were thought to be around 40,000 years old, but this was thrown into doubt by faunal evidence suggesting a Middle Pleistocene date, around 160,000 years ago. The fossils were reappraised as representing an archaic form of Homo sapiens or perhaps a population of Homo sapiens that had interbred with Neanderthals.[11] This was consistent with the idea that the then oldest known remains of a Homo sapiens idaltu, dated to around 195,000 years ago and found in OmoKibish, Ethiopia, indicated an eastern African origin for humans at around 200,000 years ago.[12]

However, dating carried out by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig revealed that the Jebel Irhoud site was far older than first thought.[2] Fresh excavations carried out in 2004 by the Hublin team revealed the remains of at least five people and a number of stone tools. The finds included part of a skull, a jawbone, teeth and limb bones which had come from three adults, a juvenile, and a child aged about seven and a half years old.[11] The bones looked similar facially to those of humans today but had much larger lower jaws and elongated braincases. They have similar features to the Florisbad Skull dating to 260,000 years ago found at the other end of the continent, in Florisbad, South Africa, which has been attributed to Homo sapiens on the basis of the Jebel Irhoud finds.[13] [11]

Jean-Jacques Hublin at Jebel Irhoud (Morocco), pointing to the crushed human skull (Irhoud 10) whose orbits are visible just beyond his finger tip.

The tools were found alongside gazelle bones and lumps of charcoal, indicating the presence of fire and probably of cooking in the cave. The gazelle bones showed characteristic signs of butchery and cooking, such as cut marks, notches consistent with marrow extraction, and charring.[12] Some of the tools had been burned due to fires being lit on top of them, presumably after they had been discarded. This enabled the researchers to use thermoluminescencedatingto ascertain when the burning had happened, and by proxy the age of the fossil bones, which were found in the same deposit layer. The burnt tools were dated to around 315,000 years ago, indicating that the fossils are of about the same age. This conclusion was confirmed by recalculating the age of the Irhoud 3 mandible, which produced an age range compatible with that of the tools at roughly 280,000 to 350,000 years old. If they hold up, these dates would make the remains by far the earliest known examples of Homo sapiens.[7] [1] [14]

This suggests that, rather than arising in East Africa around 200,000 years ago, modern humans may already have been present across the length of Africa 100,000 years earlier. According to study author Jean-Jacques Hublin, "The idea is that early Homo sapiens dispersed around the continent and elements of human modernity appeared in different places, and so different parts of Africa contributed to the emergence of what we call modern humans today."[13] Early humans may have comprised a large, interbreeding population dispersed across Africa whose spread was facilitated by a wetter climate that created a "green Sahara", around 330,000 to 300,000 years ago. The rise of modern humans may thus have taken place on a continental scale rather than being confined to a particular corner of Africa.[15]

Other findings

When comparing the fossils with those of modern humans, the main difference is the elongated shape of the fossil braincase. According to the researchers, this indicates that brain shape, and possibly brain functions, evolved within the Homo sapiens lineage and relatively recently.[13] [7] Evolutionary changes in brain shape are likely to be associated with genetic changes of the brain's organization, interconnection and development[16] and may reflect adaptive changes in the way the brain functions.[1] Such changes may have caused the human brain to become rounder and two regions in the back of the brain to become enlarged over thousands of years of evolution.[1]

Seealso

• Fossil

• Humantimeline

• Life timeline

• List of fossil sites (with link directory)

• List of human evolution fossils (with images)

• List of transitionalfossils

References

1. Zimmer, Carl (7 June 2017). "Oldest Fossils of Homo sapiens Found in Morocco, Altering History of Our Species". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

2. Callaway, Ewan (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species' history". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22114. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

3. "Oldest Homo sapiens bones ever found shake foundations of the human story". The Guardian. 6 July 2017. "Hublin concedes that scientists have too few fossils to know whether modern humans had spread to the four corners of Africa 300,000 years ago. The speculation is based on what the scientists see as similar features in a 260,000-year-old skull found in Florisbad in South Africa."

4. Shaw, Ian; Jameson, Robert (2008). A Dictionary of Archaeology. John Wiley& Sons. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-470-75196-1.

5. "Le JbelIrhoud livre peu à peu ses secrets". L'economiste.com. 1 June 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

6. Lewino, Frédéric (7 June 2017). "Découverte exceptionnelle par un Français d'un sapiens de 300 000 ans". Le Point. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

7. "Scientists discover the oldest Homo sapiens fossils at Jebel Irhoud, Morocco". Phys.org. 7 June 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

8. Hublin, Jean-Jacques; McPherron, Shannon (2012). Modern Origins: A North African Perspective. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 111. ISBN 978-94-007-2928-5.

9. Ennouchi, Émile (1962). "Un neandertalien: L’Homme du JebelIrhoud (Maroc)". Anthropologie (66): 279–299.

10. Ennouchi, Émile (1962). "Un crâne d’Homme ancien au JebelIrhoud (Maroc)". Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences (254): 4330–4332.

11. Hublin, Jean-Jacques; Ben-Ncer, Abdelouahed; Bailey, Shara E.; Freidline, Sarah E.; Neubauer, Simon; Skinner, Matthew M.; Bergmann, Inga; Le Cabec, Adeline; Benazzi, Stefano; Harvati, Katerina; Gunz, Philipp (2017). "New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens". Nature. 546 (7657): 289–292. ISSN 0028-0836. doi:10.1038/nature22336.

12. Richter, Daniel; Grün, Rainer; Joannes-Boyau, Renaud; Steele, Teresa E.; Amani, Fethi; Rué, Mathieu; Fernandes, Paul; Raynal, Jean-Paul; Geraads, Denis; Ben-Ncer, Abdelouahed; Hublin, Jean-Jacques; McPherron, Shannon P. (2017). "The age of the hominin fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, and the origins of the Middle Stone Age". Nature. 546 (7657): 293–296. ISSN 0028-0836. doi:10.1038/nature22335.

13. Sample, Ian (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens bones ever found shake foundations of the human story". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

14. Yong, Ed (7 June 2017). "Scientists Have Found the Oldest Known Human Fossils". The Atlantic. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

15. Gibbons, Ann (7 June 2017). "World’s oldest Homo sapiens fossils found in Morocco". Science. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

16. "Der Homo sapiens istälteralsgedacht" (in German). InformationsdienstWissenschaft. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

External links

• Article at PhysOrg.com

• The Guardian: 160,000-year-old jawbone redefines origins of the species

• The New York Times: Oldest Fossil of Homo sapiens Found in Morocco, Altering History of Our Species

ENNOUCHI, Emile - Origines de l'homme au Maroc -, H T, 1964, T. V, fascicule unique, pp. 163-166. ENNOUCHI, Emile - L'homme du JbelIhroud.Etude de paléonthologie humaine, H T, 1963, T.IV, fascicule 1-11, pp. 229-230

(HT : HéperisTamouda, revue de la Fac de lettres de Rabat)

Safi/archéologie

Le JbelIrhoud livre peu à peu ses secrets

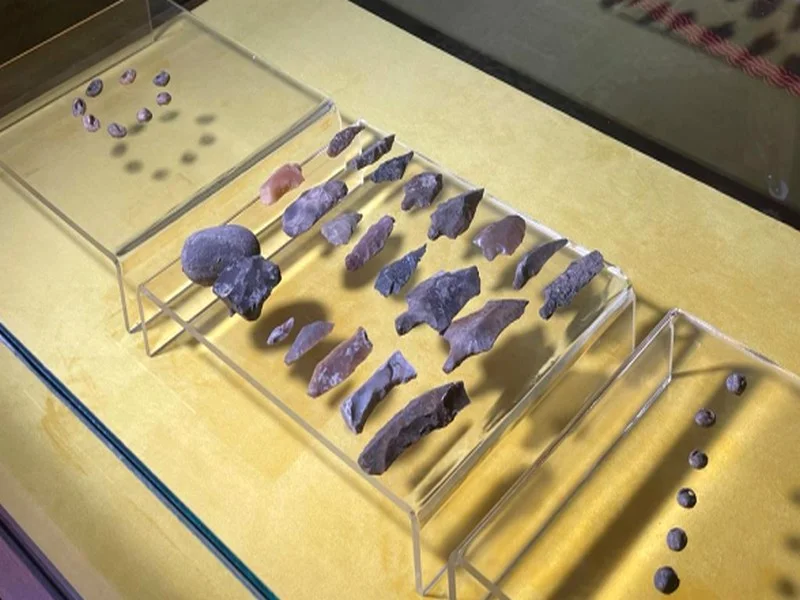

. Un crâne vieux de 160.000 ans mis à jour. Le site exploré par les archéologues depuis 1961UNE équipe d’archéologues marocains et allemands a découvert, le 26 mai, à jour le crâne d’un Homo sapiens à JbelIrhoud, dans la région de Safi. Une découverte de taille dans ce site exploré par les archéologique depuis 1961. L’expédition, menée le cadre du programme de recherche en coopération entre l’Institut national des sciences de l’archéologie et du patrimoine (Insap) et l’Institut Max-Planck d’anthropologie évolutive de Leipzig (IMP-EVA) en Allemagne, a démarré en février dernier. Ce morceau d’humain serait âgé d’au moins 160.000 ans. « Nous sommes donc en présence d’un spécimen qui serait un des plus anciens représentants de l’espèce Homo sapiens », indique un archéologue. Les datations par thermoluminescence sont en cours de réalisation pour déterminer l’âge exact de ce fossile. . Les fouilles continuent pour comprendre le présent. La montagne d’une hauteur de 592 mètres abrite la grotte d’une ancienne mine de barytine. Des fouilles précédentes sur ce gisement ont permis la découverte de restes humains dont deux crânes d’hominidés adultes et qui sont associés à une industrie levalloiso-moustérienne et d’une riche faune. Les restes humains découverts à JbelIrhoud, autrefois attribués au groupe des néandertaliens sont actuellement rattachés au groupe des homo sapiens archaïques. Les datations effectuées sur des dents animales ont donné des âges variant entre 90.000 et 190.000 ans. Ce qui ferait des hommes de JbelIrhoud les contemporains sinon les prédécesseurs des premiers Homo sapiens du Proche-Orient. Chronologiquement, c’est le chercheur français Emile Ennouchi qui avait découvert le premier crâne en 1961 et qui fut baptisé Irhoud 1. Ce dernier est actuellement exposé au musée de Rabat. En 1962, le même archéologue a pu mettre à jour une autre partie d’un crâne humain appelé Irhoud 2. Par la suite, la mandibule inférieure d’un enfant est désignée Irhoud 3. D’autres recherches menées par l’archéologue Tixier se sont succédées sur le site à partir de 1967. Il a pu répertorier 1.267 trouvailles enregistrées. C’étaient des crânes, un humérus qui a pris le nom de Irhoud 4, un os coxal (Irhoud 5) et d’autres ossements. Le matériel découvert comprend des objets archéologiques sous forme d’outils appartenant à l’âge paléolithique moyen. Déjà, des datations de ces crânes ont remonté jusqu’à 130.000 ans. Les outils, eux, remonteraient à la civilisation moustérienne.

Ce sont des lames en silex, des pointes de flèches, des couteaux à dos, des grattoirs, des perçoirs, des galets traités et autres. Des Américains ont aussi prospecté dans le site durant les années 1990. Le site désormais de renommée internationale révèle peu à peu ses secrets. En tout cas, la dernière découverte encourage les spécialistes à préserver. « Il s’agit de comprendre le présent », déclare l’un d’entre eux. Si les fossiles permettent aux paléontologues de dévoiler petit à petit le monde fascinant du temps des dinosaures, l’être humain est encore très loin d’avoir tout découvert. Mohamed Ramdani

Source Web : l’Economiste

Les tags en relation

Les articles en relation

Nos ancêtres les berbères …

Si cette petite formule avait résonné dans la tête des écoliers marocains tout du long de leur scolarité, comme ce fut le cas jadis pour les petits frança...

Maroc : découvertes archéologiques qui réécrivent l’histoire

Les récentes découvertes archéologiques au Maroc bouleversent la vision traditionnelle d’un passé réduit à ses monuments majeurs. À Volubilis, la mise ...

Archéologie: les découvertes de la grotte de Bizmoune mettent Essaouira sur la carte des sites d�

La récente découverte archéologique dans une grotte d’éléments de parure mettant en évidence le plus ancien comportement symbolique humain, a fait l'...

La plus ancienne sépulture féminine découverte en Europe est celle d’un nourrissonLa découvert

La découverte de « Neve », enterrée dans une grotte italienne à peine huit mois après sa naissance, suscite des interrogations quant au stade à partir du...

Le Maroc pourrait être proposé pour inscription comme patrimoine mondial

Le Maroc est un pays extrêmement riche en biens susceptibles d’être proposés pour inscription dans la liste du patrimoine mondial, a affirmé, vendredi à ...

Paléolithique: découverte de l'Acheuléen le plus ancien d'Afrique du Nord, près de Casablanca

Une équipe internationale a découvert l'Acheuléen le plus ancien d'Afrique du nord, datant de 1,3 million d'années, dans la périphérie de Casa...

ADN : Les plus anciennes traces à Taforalt

Une équipe internationale d’archéologues et de généticiens a découvert dans la grotte des Pigeons à Taforalt au Maroc oriental les plus anciennes traces...

Archéologie: de nouvelles découvertes sur les traces du port antique de Lixus

A Lixus, près de Larache, se trouve la plus grande unité de salaison de poisson de l'Antiquité romaine, datant de l’Ier siècle avant J.C. Une équipe ...

Ces découvertes archéologiques de 2023 qui ont bouleversé nos certitudes sur l'Humanité

L’année 2023 fut extrêmement riche en découvertes archéologiques d’envergure. Dans sa newsletter consacrée à l’archéologie et baptisée “Our Huma...

Afrique du Sud : des traces de pas fossilisées révèlent des indices sur les Homo sapiens de 76 00

Une étude récente met en lumière la découverte remarquable de plusieurs pistes d'empreintes humaines fossilisées sur un ancien champ de dunes situé su...

Sijilmassa : découverte de la plus ancienne mosquée du Maroc

Les travaux de valorisation du site archéologique de Sijilmassa, près de Rissani (province d’Errachidia), ont révélé une découverte majeure : les vestig...

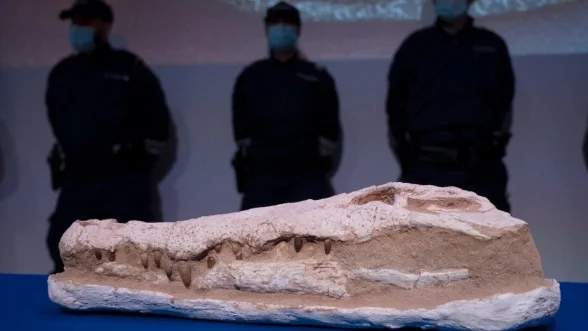

Le Maroc récupère 20 pièces archéologiques datant de la période préhistorique

L’université de Bordeaux a restitué à l’Institut national des sciences de l’archéologie et du patrimoine 20 objets, représentant des restes humains, ...

mardi 31 octobre 2017

mardi 31 octobre 2017 0

0

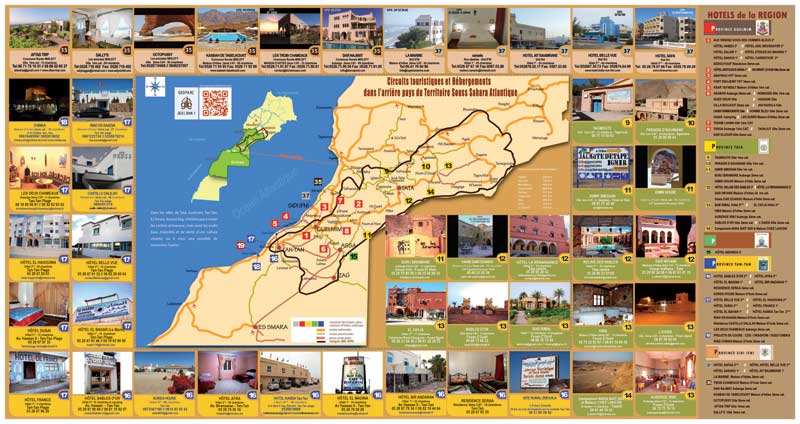

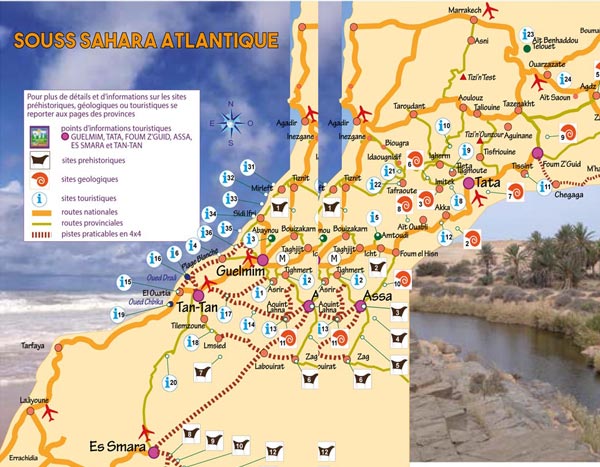

Découvrir notre région

Découvrir notre région