In Search of Ancient Morocco South of Marrakesh, the Draa Valley still exerts an indefinable pull, retaining traces of its now almost-vanished Berber kingdom.

THE SHAMROCK GREEN of Casablanca graded into a flat plain of beige. From the tarmac itself, I could see the beige run into a towering wall of white — the Atlas Mountains. Edith Wharton, in her 1920 travelogue, “In Morocco,” had felt herself fall under the spell of the Atlas and the desert beyond as well. “Unknown Africa,” she writes, “seems much nearer to Morocco than to the white towns of Tunis and the smiling oases of South Algeria. One feels the nearness of Marrakech at Fez, and at Marrakech that of Timbuctoo.”

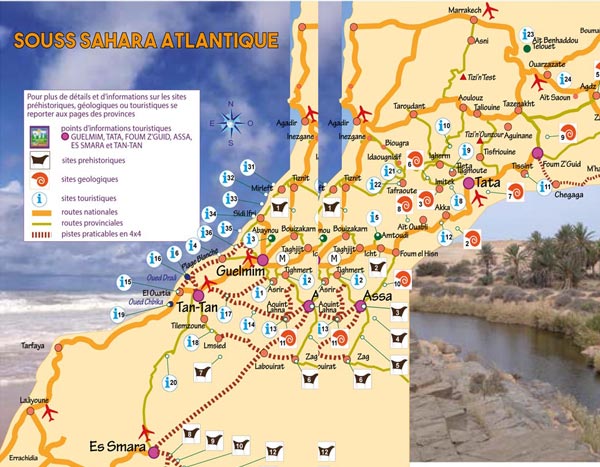

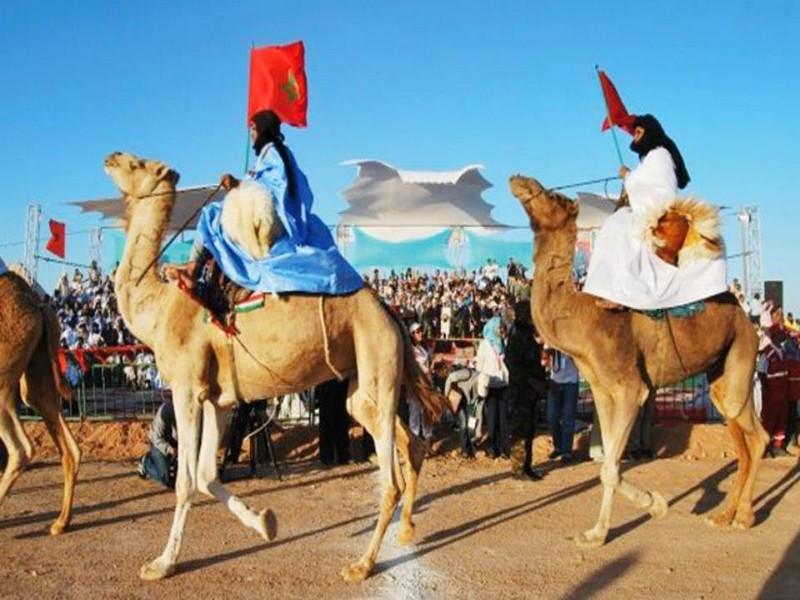

To be in Marrakesh on that morning in late February was to feel the nearness not of the Sahara but of Stansted and Orly. The “great nomad camp” of the south — which had once attracted the Tuareg, the West African tribe who had plied the caravan route through the Sahara since at least the fifth century B.C. and were known as “the blue people” of the desert because of their indigo-dyed robes — was awash with the tourist trash of Europe — the EasyJet set. This was a city where glamorous European families, such as the Agnellis, owned houses, where the name of the garden designer Madison Cox, the widower of Pierre Bergé (Yves Saint Laurent and his partner, Bergé, had fallen in love with Marrakesh in the 1960s) was whispered like a holy name among the demimonde. It was impossible now to smell Timbuktu in Marrakesh. Colonial boundaries and modern tensions — the border with Algeria has been permanently closed since 1994, after a conflict broke out between the two countries — had pushed the desert back. One had to go much farther south, across the Atlas and into the Draa Valley, an 8,900-square-mile oasis that ran along the Algerian border, to get a whiff of that world to which the exchange of goods and ideas — first salt, silver and slaves, then religion, manuscripts and notions of kingship — had given an inner cohesion. A Persian friend in New York, a man of taste and refinement, had spoken to me one evening of the Draa. He told me of medieval Islamic libraries in small Saharan towns, of shrines to desert saints and of old Jewish houses.

[Coming soon: the T List newsletter, a weekly roundup of what T Magazine editors are noticing and coveting. Sign up here.]

I wanted badly to go. I was mourning an impression of Arabia that I had received 10 years before, while traveling in the Hadhramaut region of Yemen, known for its key position on the incense trade, and researching my first book, “Stranger to History: A Son’s Journey Through Islamic Lands” (2009). I feared that civil war in Yemen in recent years had laid waste to that fairy-tale ideal of crenelated mud-walled cities set in a belt of blue date palm, full of cool and shade. It may be odd to go to one place in search of another, but so much has been lost of late, here in the spread of a homogenizing modernity, there through the destruction of ancient sites in places like Bamiyan in Afghanistan and Palmyra in Syria. Our time is the enemy of the past, and increasingly I find the wonder of travel lies less in the discovery of new places than in tracing the outline of those that have ceased to exist.

The desert wilderness between the towns of M’Hamid and Foum Zguid in southern Morocco. Credit Richard Mosse

IT WAS A RELIEF to see Monsieur Azzdine — burly, bearded, bespectacled, all flesh and blood, with a chipped-tooth smile and a predilection for Winston cigarettes — materialize out of the speculative haze of a WhatsApp chat. He had come to me as men only can in our time. A year before I met a handsome Moroccan yogi on an Etihad Airways flight to Delhi, India. We became fast Instagram friends. When I needed a driver to take me south into deepest Morocco, it was he who suggested Azzdine. Soon we were all on a WhatsApp group chat titled “Maroc.” Once the recipient of the French prize at college, I now speak an execrable but energetic French, full of unwarranted ambition. When Azzdine expressed fears about le sable, I thought, “Le sable?” dimly recollecting the title of a 1985 novel by the great Moroccan writer Tahar Ben Jelloun: “L’Enfant de Sable.” “The Sand Child” … aah no, I assured Azzdine, it was not the sand of the Sahara I was after but the world of the Sahara. We agreed on a price and arranged to meet at Marrakesh Menara Airport.

We made a brief gas stop at an Afriquia station, and then we sped out of the pink city, whose streets were lined with orange trees, their fruit-laden canopies pruned into perfect cubes. I caught flashes of bougainvillea in deep shades of cerise framed against a sky of such intense blue that even the French Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix, in 1832, had not attempted to paint it until his return to France months later. We ascended into the Atlas, heading southeast via the Tizi n’Tichka, a road renowned for its sweeping vistas and sharp spiraling gradient.

The girdle of the Atlas Mountains that gives Morocco its crooked spine had also served as a barrier of sorts between worlds. The bled al-makhzen, the region of law, lay on one side; the bled al-siba, literally the “region of anarchy,” lay on the other. These were precolonial distinctions that divided the area under the rule of the 17th-century Alaouite dynasty from the ungoverned tribal area in the south that had not submitted to its authority. Half this humpbacked country faced the sea, from which the influence of Phoenicia, Carthage and Rome had washed over it; the other half gazed out at an ocean of sand, no less a world unto itself. Out of the east had come Arabia and Islam, blending with the oldest element in Morocco’s syncretic character — the Berbers. These were the indigenous inhabitants of North Africa who spoke Afroasiatic languages, a world away from Arabic, and who practiced various animist cults. Their history, their language, their dress and customs served as a link to the ancient past of the land, as distinct from the history of the Islamic faith brought about by the successive waves of conquest starting in the seventh century.

The river Oued n’Fis snakes past a small town in the High Atlas.

“There’s no mere landscape,” J.M. Coetzee said in 2001, firmly putting down an interviewer who wished him to move “beyond questions of mere landscape.” In Morocco, I understood the meaning of these words, for the landscape grew so varied that it seemed almost to stand as a kind of shorthand for the country’s myriad natures. The ferric red of Central Africa appeared in furrowed hills covered in sparse emerald grass. Ahead, in the same frame, was a Swiss pine forest that led up to high craggy mountains, with peaks of waxy sunlit snow. The burnt shrub-covered hills of a Greek island played host to great stockades of flowering cactuses. Dense clotted argan, dark verdure against dark earth, appeared alongside slim-limbed almond blossoms, their canopies feathered white. The gorges were silvered with lush olive groves that owed their fertility to brawling streams, thin as ribbons. These impossible combinations, this infinite variety — all this, and not any one thing, was Morocco. It felt as if the earth was tearing at its seams, revealing the full range of its possibility, continents colliding into one another, all in anticipation for the nullity and open sky of the desert.

It was evening when the Tizi n’Tichka spat us out onto a road that led down to an arid plain near Ouarzazate — known as “the door to the desert” — 120 miles southeast of where I had first landed in Marrakesh. The westering sun penciled the furrows of the red hills. A chill silence spread over the land. This was the likely setting for that most frightening of all of Paul Bowles’s stories, “A Distant Episode” (1947), in which a professor, soon to have his tongue cut out, descends from a “high, flat region” at evening toward a “flaming sky in the west” and “sharp mountains.” Bowles lived much of his long, louche life in Morocco, where in between parties and rent boys, he received droves of ardent fans from the United States. The late New York painter and poet Rene Ricard visited him in Tangier and told me that as one Moroccan boy more beautiful than the next appeared — now at the petrol station, now at a carpet shop — Bowles would kiss him on the forehead and, turning to Ricard, say, “I used to know his father.”

A tourist camp set up in one of the more remote regions of the desert. Credit Richard Mosse

M’HAMID IS THE LAST town in Morocco before the Algerian border. The road doesn’t so much take you there as simply runs into the sand. On the afternoon of the second day, we arrived at a small hotel called Dar Paru. It was the last property along a dirt road lined with mud-brick villages. Paru was a German proprietor who had adopted her Sanskrit name upon becoming a renunciant. She sat outside in the late afternoon sun, an older woman with a shock of white hair, drinking tea and examining a map.

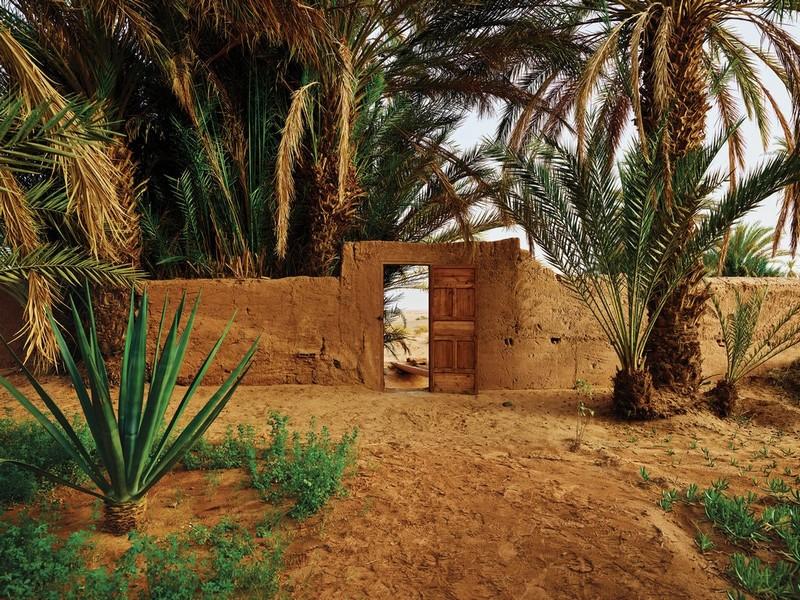

“Have you seen our door to the Sahara?” she said with a strange smile.

We sat in a lush garden of olives and date palms. It seemed inconceivable that the desert could be so close. Paru directed me to a door at the far end of a walled garden. I opened it and there, in the crude door frame, was the boundless expanse of crescent dunes edged with sharp black lunettes. It was arresting, unspeakably beautiful, and yet I felt an odd sense of trepidation at finding myself in this empty hotel on the edge of a desolation almost the size of the United States.

“What brought you here?” I asked Paru.

“My inner voice,” she replied easily.

Paru then began to speak of the desert fathers and of marabouts, holy men who, in these parts, had used the desert as a site of spiritual inquiry. She spoke with intensity of shrines to these men in ancient villages that bordered the Sahara. “They found freedom,” Paru said. “They found their spirituality without the Quran, without anything. Just through their insight.”

The exterior of a shrine near the 17th-century Tamegroute library, home to one of the most important Quranic collections in the world.

The Draa Valley runs along the Algerian border.

The dictates of Paru’s loud “inner voice” had made her leave her husband in Germany in the mid-1990s and come, via Spain, to this place in the desert. Upon seeing the property, she collapsed in tears, overpowered by a feeling of recognition. She recalled panic seizing her on a trip in the desert with the Berbers. Not religious, and certainly not Muslim, she found herself uttering the first part of the Islamic proclamation of faith — La illaha illa Allah: “There is no God but Allah” — again and again. She resisted the full formulation, “but,” she cried, as if still surprised at how the testament of faith had come to her unwilling lips, “it belongs, doesn’t it?”

And so, Paru said the rest — Muhammad rasul Allah: “Muhammad is the messenger of Allah” — till her fear was gone. It was as if she had invoked the protection of a monotheistic faith against a holy terror that seemed to emanate out of an older world of pagan worship.

That night, I would know fear of my own. We say we travel to experience, and yet when real experiences come our way, especially those that are not easily explained, the traveler hesitates to record them.

Darkness fell. I ate a tagine of meatballs alone in a firelit room. Paru joined me for dessert, then I retired into a small high-ceilinged room, narrow as a coffin, with a bed draped in a white mosquito net.

At about 1:30 a.m., I awoke in terror. My body was frozen, as if pinned down by an invisible force. Cold spasms ran up my spine. I had trouble breathing and the darkest visions engulfed my mind. I was neither asleep nor awake but in some kind of half state. I tried as best I could to turn my mind to all the positive things in my life, my husband, my dog. Yet all that was good went bad, returning to me in the image of my fear, which was physical and prehensile, like a swarming of nerves. Paru herself appeared to me as a witch doctor, a sorceress. It was then, recalling the story she had told me, that I found myself uttering the same words she had used to ward off her fears: La illaha illa Allah, Muhammad rasul Allah …

It was the first time in my adult life that I had prayed.

The Anti-Atlas looms in the background of the Draa Valley. Credit Richard Mosse

IN THE MORNING, I did not speak of what had occurred the night before to Paru. But I was determined to get away. We spent the morning driving through barley fields, edged by the Sahara. Paru pointed out the squarish shrines with domed ceilings, framed against the ribbed surface of the open desert. The nearness of Timbuktu — still 52 days away by camel, one sign read — which was the epicenter of trade and culture on the trans-Saharan caravan route and a fabled name in the Western imagination, was palpable in M’Hamid. I felt I stood at the periphery of an interconnected world of worship and belief.

It was disturbing to think of oneself as rational and irreligious but to have an experience that felt supernatural. Nothing remotely close to this had ever happened to me before. I had laughed at those who claimed to see ghosts or be unnerved by the energy of a place. I had no means to understand what happened at Dar Paru, nor did I want to make a place in my life for magic. It was unassimilable, my night in the Sahara, and it left me disquieted and full of doubt. I could not believe, but I would never mock again with so much conviction.

That afternoon, some 45 miles north, at Tamegroute, a fly-bitten town along a dusty road, I was given a glimpse of the lines of transmission that had once connected the defunct world of the Sahara. Here, where a community of potters still produced the tiles whose manganese green glaze evokes eternal scenes of Morocco and Muslim Spain, and where a few urchins stood around a square, playing at being muezzins with long pieces of piping, Sidi Mohammed ibn Nasir, a religious teacher and physician, had established a Sufi order called the Nasiri brotherhood in the 17th century. Nasir had made a vast collection of manuscripts redolent of the private libraries of Timbuktu that Al Qaeda-allied fighters tried to destroy in 2013.

The library had closed for a midday break, but Azzdine had the presence of mind to pay a small bribe to one of the local guides. A bit of theater ensued. We were told the guardians of the library — two men, each bearing a different set of keys — were on their way.

“Voilà,” cried Azzdine, stubbing out a Winston, at the sight of an old man with thick black sunglasses, Ray Charles in a djellaba, who came gliding onto the central square in a wheelchair. He wore a crocheted skull cap of white and gold and a giant hearing aid. This august toothless figure was the senior guardian. He was soon joined by a younger man, who arrived, stage left, on a BMX. The two keepers of the keys opened the doors of the great library in succession, and, seconds later, we were in a treasure house of medieval learning.

“Pythagore!” the old deaf librarian yelled at me, as I gazed vacantly down at an Arabic translation of the Greek mathematician’s work. There were works of botany and astronomy, a magnificent medieval Quran inscribed on peau de gazelle. The library once held some tens of thousands of manuscripts. That number had declined of late — the works were scattered in museums elsewhere — but the library itself stood as an outpost of learning at the edge of a vast emptiness.

The hearth at hotel Dar Paru.

Members of the Draa Valley’s animal population.

ABSENCES CAN EXERT a gravitational pull. That afternoon, Azzdine and I drove for hours along the circumference of one of the greatest absences known to man. The Sahara, though now out of sight, was behind a line of red mountains — the Jbel Bani, a low, arid mountain range that runs like a sea wall on the southern side of the Anti-Atlas — whose striated surfaces formed whorls, as if bearing the impression of enormous thumbprints. The lines brought a feeling of continuity, as did the belt of blue palms. Now and then on the burning plain there would be a single Acacia raddiana, a squat, flowering desert tree, its umbrella-shaped canopy casting a tantalizing pool of shade.

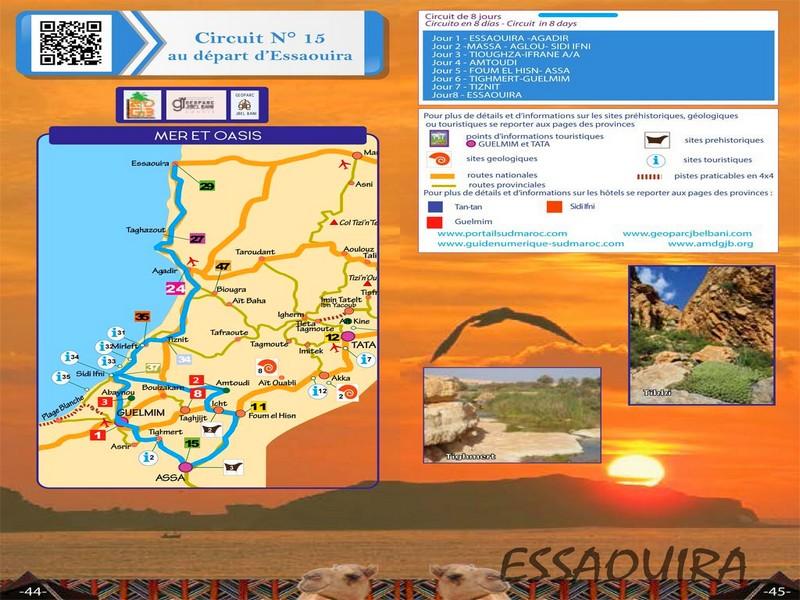

In New York, I had heard of a Frenchman called Patrick Simon, an autodidact with an encyclopedic knowledge of the Draa. I had been trying to track him down for days. The man I found that evening, sitting on the roof of a ravine, on the telephone, a silk scarf around his neck, had lived more lives than are possible to enumerate. Simon, who had been in Morocco for over 40 years, had by turns been a decorator, an actor, a hotelier and a conservationist. He was in his 70s now, a short man with an elfin face and boundless energy. His signature achievement is a geo-park, a conservation area that encompasses 46,300 square miles of the Draa Valley, from Tantan, on the ocean, to Zagora, deep inland.

“If there is one living oasis in the world,” said Simon, holding up a flat-palmed hand on which he, a widower, still touchingly wore his wedding ring, “it is this one.” He described Morocco itself as a pivot, a place where Europe, Africa and Arabia coalesce. Tissint, the Draa town nearest to us, where Simon had set up an encampment of brown Bedouin tents, means “salt” in Berber. It was the key commodity in the trade that had stitched together the Sahara. The Berber element had grown stronger as we drove deeper into the Draa and, racially speaking, we were in a region that was much nearer to sub-Saharan Africa than Arabia. Simon explained that it was the Arabs who had brought the date palm to this region, thus establishing the economy of the oasis, and ensured the spread of Islam.

“Who was here before?” I asked.

“Ancient Jewish, Berber and Christian communities, as well as animists,” Simon answered.

A Jewish community had still been here in Wharton’s time — “Jews abounded in the market-place and also in the town” — working the silver trade and living in ghettos, “into which,” Wharton writes, they were “locked at night, as in France and Germany in the Middle Ages.” In the postwar years, some quarter of a million had immigrated to Israel, Europe and America.

A lush oasis foregrounds the mountains in Aagoubt in the Draa Valley. CreditR ichard Mosse

Abdel Majid, a spruce Berber youth in his 20s who worked for Simon, promised to show me the quartiers juifs, the neighborhoods of small Draa towns where the Jewish community had traditionally worked and lived. Abdel Majid, who switched effortlessly between French, Arabic and Berber, seemed to carry within him the three-tiered history of Morocco.

It grew dark. The sky was encrusted with thick clusters of stars. Simon opened some white wine and we sat by a fire talking about the tension that exists in Muslim countries between the pre-Islamic and the Islamic past. “The time before Islam,” V.S. Naipaul writes in “Among the Believers: An Islamic Journey” (1981), “is a time of blackness: that is part of Muslim theology. History has to serve theology.” I had been in Morocco scarcely a few days, and I felt already as if I had entered a sphere of deep atavisms and belonging. It was as if the pre-Islamic Berber past breathed easily next to the Arabized country — and yet the Berber history, old beyond conception, was a source of wonder even to someone like Azzdine, who was married to a Berber woman. People spoke of their Berber roots in Morocco, almost as if speaking of an unknown part of their nature. In the streets of Draa towns, the diptych of Arab and Berber, as Abdel Majid pointed out the next day, was enshrined in the dress of women. The Berbers wore brightly colored skirts, velvety blouses and headdresses, known in parts as idgharn, while the Arab women wore wonderful floral or tie-dyed imelhafen, all cut of a single cloth.

Abdel Majid, Azzdine and I were on our way to see the Jewish quarter in a small Draa town called Akka, 80 miles southwest of Tissint. The delineation of absence had been my theme as I traveled through the Draa, along the perimeter of a void, to which men through the traffic of commerce and thought had brought unity. On my last morning in the Draa, I was granted a glimpse of the empty house of a community that had once formed an integral part of a now shattered wholeness. There were Jews in Morocco who had come to the country after they were expelled from Catholic Spain in the 15th century, but the Jews of the Draa were a far older community, composed of merchants and artisans, with roots in the region that stretched back to at least the second century. Abdel Majid pointed out the small doors that were apparently typical of communities that worked with silver; he showed me the craggy mud-brick buildings and the narrow, shaded streets, now moraines of trash; but none of this spoke to me of the Jews of Akka. Then, by pure chance, we stumbled upon a house whose walls had been torn away. Located above an alcove were shreds of ornamented stucco, now in a T-shape, now in a circle. One was covered in tiny circles of blue, white and brown; the other, in blue almond-shaped leaves against a white background. What were they, these strange mystical symbols? They seemed almost to be part of an ancient game board or mandala — so abstract, so suggestive, so moving in their determination to remain as material proof of those who had departed.

On the Cover: Tinmel Mosque, which was built in Morocco’s High Atlas Mountains in the 12th century, was once at the heart of the region’s Berber-Muslim Almohad empire. Morocco is featured in T’s May 19 Travel issue.CreditRichard Mosse

THE THEME OF exile and absence followed us to Taroudant, which sat in the shadow of the Atlas, now just a violet outline, 140 miles southwest of Marrakesh. It had been a surreal journey, in which I had let people and experiences come to me, as they would, resisting nothing. And it was to take one last surreal turn. My Persian friend in New York, who had first told me of the Draa, was an intimate of the last empress of Iran, Farah Pahlavi. As I entered my fifth day of being filthy and unshaven, with scarcely a clean T-shirt let alone a jacket or formal shoes, I received a direct message from him: “I was just contacted by H.M. Queen Farah, and she asked you to come to dinner tomorrow.”

A discreetly lit blue door led into a pleasure garden where night-blooming jasmine wafted through the night air. In a great room, decorated with candlesticks of dull brass and ostrich eggs in bowls, a fire burned on one end and a floodlit swimming pool was visible through glass doors. A phalanx of silver-framed photographs of the last Shah of Iran was arranged along a sideboard. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and his wife Farah had left Iran in 1979 after the Islamic revolution that brought Ayatollah Khomeini to power forced them out. The shah died soon after of cancer, while Farah began a long exile in Egypt, the United States and Paris. She bought her mud-brick house in Taroudant, where she came several times a year, because it reminded her of the country to which she longed to return. Soon the shahbanu-in-exile (“shahbanu,” which means “empress” in Persian, was created expressly for Farah) would appear, still radiant at 80, with black ribbons in her gold hair and corals on her neck. Soon there would be a wonderful dinner, full of friends and family, where talk would turn inexorably to exile and revolution and elites pushed out of countries that were changing too fast. Soon, over a table laden with Persian rice, the last empress of Iran would turn to me and say, “In exile, food becomes important.” Soon Mowgli, Her Majesty’s King Charles spaniel, would shower me in kisses. Soon I would be left with an odd feeling of melancholy at having met one of the legendary figures of the 20th century, this lady who retained an almost girlish sense of innocence and humor, despite having lived through the loss of countries and children, and more experience than several lifetimes could encompass. Soon there would be all this, but before I walked through that door and civilization returned with all its force, I found it hard to let go of the image of that other door to the Sahara in Dar Paru.

My Persian friend in New York had spoken of the persistence of magic in Morocco, and of a sphere where the old gods were yet to be overthrown. In Taroudant, I knew I would be leaving this sphere behind me, climbing up into the mountains, back into the bled al-makhzen, the region of law. The world of Islam would return, grafted thinly upon a core of older belief — what Wharton calls the “old stone and animal worship, and all the gross fetichistic [sic] beliefs from which Mahomet dreamed of freeing Africa.” Even from the great mosque at Tinmel, once the Almohad capital, it would be impossible to re-enter the feeling I still had as I stood in that great house on the other side of the Atlas.

It was a feeling of vacancy, of being emptied out by the desert. The silence we had come out of — and which made Azzdine exclaim, “Le radio enfin,” as a remix of “Bella Ciao” blared, announcing our arrival in Taroudant — was fading. Variety had returned, erasing the shattering sameness of the plain against which every little tomb and tree was amplified into a focusing point for the eye and the spirit. For one brief moment, I stood in a liminal place. Ahead was a door to a brightly lit room full of laughter and cheer; behind me was Paru’s door to the Sahara; and all around me, in my bones, I knew, as perhaps I may never know again, the power of the desert as a spiritual resource. I am not a spiritual person; I am devoted to concrete reality. And it frightened me. I had an intimation of the fragility of the bled al-makhzen — the sphere men create to keep at a safe distance the perturbation beyond, should one step through the wrong open door.

Local Production by Fred Fantun.

Le May 15, 2019

Source web Par nytimes

Les tags en relation

Les articles en relation

Collectivités territoriales: des caisses bien remplies

La situation provisoire des charges et ressources des collectivités territoriales dégage un excédent budgétaire de 4,4 milliards de dirhams à fin juillet 2...

Le Roi désigne de nouveaux objectifs à l'agriculture: classe moyenne rurale, jeunesse et emploi

En ouvrant la nouvelle session parlementaire, le vendredi 12 octobre 2018, le Roi Mohammed VI a donné une nouvelle impulsion à l'emploi et à la jeunesse ...

L’état de Khadija, “la fille aux tatouages”, se détériore

L’affaire a défrayé la chronique en août dernier au Maroc. Khadija Oukarrou, l’adolescente de 17 ans qui a été sauvagement violée il y a environ deux ...

#MAROC_GEOPARCS_GEOPARC_M_GOUN_GEOPARC,_JBEL_BANI - Le Maroc est un paradis pour les géologues et l

L’ouvrage traite l’évolution en quatre chapitres. Le premier chapitre traite de la formation et l’expansion de l’Univers. Le deuxième chapitre est sur...

Anti-Atlas: Un PPP pour le «Géoparc» Jbel Bani

L’idée est d’obtenir ce label de l’Unesco délivré à un territoire au patrimoine géologique remarquable Universitaires, professionnels du tourisme,...

les regards de l'AMDGJB CHARLES DE FOUCAULD, Révélation marocaine ARTE

Par cette « INVITATION AU VOYAGE de la Chaine Franco-Allemande, ARTE sur une Idée d’ ELEPHAN DOC « CHARLES DE FOUCAULD – REVELATIONS MAROCAINES » Par le...

Tourisme : Sajid réunit les acteurs marocains à Rabat

Infomédiaire Maroc – Le ministre du Tourisme, du transport aérien, de l’artisanat et de l’économie sociale, Mohamed Sajid, a tenu jeudi une séance de ...

Efficacité énergétique : On est loin du compte Etat et hommes d’affaires interpellés

«Le Maroc accuse un retard important en matière d’efficacité énergétique. En fait, ce chantier avance lentement à l’inverse des projets d’énergie...

Tourisme: La chute de la livre turque n’a pas fait augmenter le nombre de visiteurs marocains

La chute de plus de 40% de la livre que subit la Turquie depuis le début de son bras-de-fer avec les Etats-Unis est, en théorie, censée profiter aux touriste...

STATISTIQUES SUR LE TOURISME AU MAROC POUR LE MOIS D'AOUT 2018

STATISTIQUES SUR LE TOURISME AU MAROC POUR LE MOIS D'AOUT 2018 Le 25 octobre 2018 Sou...

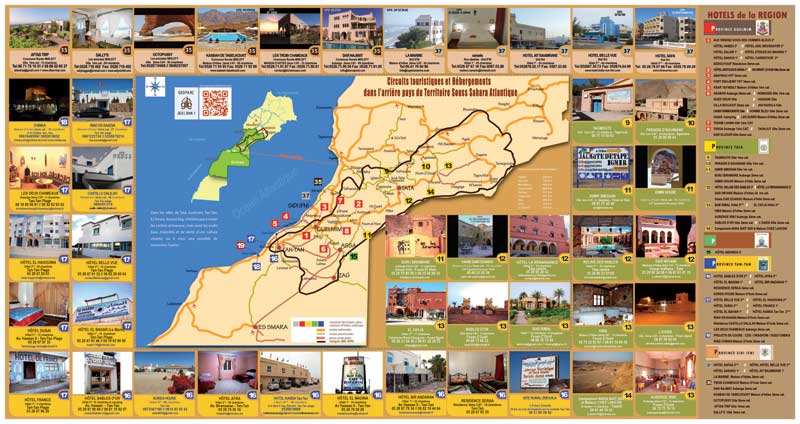

Circuit territoire soutenable du Géoparc Jbel Bani : Circuits Fascination Anti-Atlas

NB : Cliquez sur ce lien pour afficher la carte avec les informations interactive sur la carte chaque point . Pour simple Berline : Tiznit - Bou Izaka...

En vidéo : L’expérience touristique à la découverte de la région Guélmim Oued-Noun

La région Guelmim Oued Noun est l'un des douze territoires administratifs du nouveau découpage territorial Marocain arrêté en 2015. Elle s'étend su...

mercredi 28 août 2019

mercredi 28 août 2019 0

0

Découvrir notre région

Découvrir notre région